Nobel

Nobel Diesel

From a publication from 1922 from Institute of Marine Engineers.

By BARON GEORGE J. STEINHEIL, B.Se., M.I.N.A., M.I.Mech.E, M.I.A.E. (Member).

In July, 1897, Dr. Rudolf Diesel, of Munich produced in conjunction with the Maschinenfabrik Augsburg the first engine bearing his name. The experimental work to produce a commercially possible engine from the original design took about eight years to accomplish, but by July, 1897, according to Dr. Diesel’s statement, the experimental stage was finished and drawings of the engine were sent to the drawing office of the Augsburg works, in order to start manufacture on a commercial scale. There was a considerable amount of controversy in this country as well as in Germany, whether the Diesel engine was actually Dr. Diesel’s invention or not, and whether it should be called by any rival name or simply a “ high compression oil engine.” It is not the subject of this paper to discuss the vexed question, as to do this, references would have to be made to patents, to transactions of various technical societies in this country and on the Continent, etc.

However, it is enough to say that the engine developed by Dr. Diesel bears in everyday engineering life his name, and therefore the author proposes to call it by such in the paper. As soon as the first commercially practical engine was ready, representatives of various engineering concerns came to Germany to witness the tests of that engine with a view of obtaining the manufacturing licences for that type of engine for their respective works. Among those who saw the tests of this first engine was Mr. Anton Carlsund, at the time chief engineer of L. Nobel, Ltd., of Petrograd. He immediately appreciated the great possibilities of the new prime mover, especially from the Russian point of view, as in Russia the natural oil supplies were very great and incidentally practically the whole of these were controlled by Nobel interests. On his return to Russia he persuaded Mr. Emanuel Nobel, the head of the Nobel concern to acquire a licence for Diesel engines for Russia. In autumn 1897 all licence arrangements were completed and Nobels proceeded at once to build their first Diesel engine. All this happened 25 years ago.

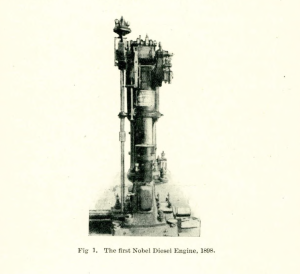

Thus the Nohel Works were among the very first firms in the world to take up Diesel engine manufacture, and among other pioneer firms may be mentioned such well-known concerns as Mirrlees, Watson, Co., Ltd., of Glasgow, now better known as Mirrlees, Bickerton and Day, Ltd., of Stockport; Maschinenfabrik Augsburg A.G.; Fr. Krupp, Germania Werft, Kiel; Care la f'reres, Ghent; Sulzer Bros., Winterthur, and others. It must, however, be admitted that the German Diesel engine of 1897 was found to be in many details quite unsuitable for Russian conditions, and the Nobels had the heavy task of re-designing the engine to suit these local conditions. Of the most important alterations were those of the fuel pump and pulveriser. The German engine was designed to work on paraffin, but the abundance of cheap raw naphtha (crude oil) in Russia, made it necessary to make the Russian engine to work on that fuel, and therefore the fuel pump and pulveriser had to be altered accordingly. In general outline, however, the Nobel engine followed closely the German design which was of the single cylinder stationary crosshead four-stroke cycle type, developing 20 b.h.p. at 200 r.p.m.. The cylinder dimensions of the engine were:-—

Diameter 260 m/m. (10-¼ in.) and stroke 410 m/m. (16-⅛ in.). Fig. 1). Tests carried out on this engine by Professor G. Doepp, of Petrograd Institute of Technology, in 1899, showed that the engine easily developed as much as 25 b.h.p. at a fuel consumption (crude oil) of 220 grams (0-486 lbs.) per b.h.p. hour with a colourless exhaust*. In 1900 a new type of 30 b.h.p. per cylinder crosshead engine was put on the market, built in one and two cylinders per shaft. The first customers for Nobel engines were the Nobel Bros. Petroleum Production Co., and the Russian War Office, while the general public and even the majority of engineers of the time looked upon the new engine with considerable suspicion. Several engines were put in the Nobel Oil Refinery at Baku in 1900. The management of the Caucasian Railways, who were then busy building the great pipe-line from Baku, on the Caspian Sea to Batum on the Black Sea, a distance of about 500 miles, for the conveyance of paraffin (kerosene), decided to install Diesel engines in their pumping stations on the pipe-line. Their decision was influenced by the great economy of a Diesel plant and also by the lack of suitable feed water for boilers of steam engines in the Baku district. The first pumping station at Baku was to be of three pumping sets of 100 b.h.p. each. If steam engines were to be installed the fuel oil consumption per station per annum (4,000 working hours) would have been about G50 tons, assuming IT lbs. of oil per h.p. hour, whereas a Diesel plant of the same power would consume about half of that amount.

Owing to the lack of fresh water supplies in Baku, the question of cooling of Diesel engine cylinders presented certain difficulties, but eventually it was decided to use the cooling water in a closed circuit, the outlet water entering a special watercooler, from which it was pumped again into the water jackets of Diesel engines. The cooling medium for the circulating water was the paraffin, which was pumped by the engines through the pipe line, the cooler having been connected for the purpose with the main pipe. In the semi-tropical climate of Caucasia this arrangement was considered more efficient than ordinary cooling towers. A new type of Diesel engine was designed for the purpose of developing 100 b.h.p. in two cylinders. The crosshead was abolished and ordinary trunk pistons were used. Three such sets were installed at Baku pumping station in 1902, and gradually all the other pumping stations on the pipe line were lniilt and fitted with Diesel engines. Bv 1903 ten different sizes of Diesel engines were already marketed bv Nobels in powers ranging from 10 to 100 b.h.p. per cylinder. The 10 b.h.p. single cylinder stationary engine was specially brought out to meet the demands of farmers and small power users. Another interesting instalation of three sets of single cvlinder trunk piston engines of 75 b.h.p. each was made in 1902 at the Tenteleff Chemical Works, of Petrograd. These engines were driving air compressors supplying air for the manufacture of sulphuric acid, and the nature of the work demanded continuous working of several davs’ running. To prevent excessive corrosion all exposed bright parts of the engines were coated with paint. It is quite possible that in future, rustless steel will be used by Diesel engine makers for this kind of work. In those early davs it was rather difficult to get Diesel engines t- I t o cv built on a manufacturing basis, as practically even* engine made was an improvement on the previous one. On the original 20 b.h.p. Diesel engine the injection air was sucked from the atmosphere and compressed to full blast pressure of 50-60 atm. (700-850 lbs. per sq. inch) in a single stage air compressor direct driven by a rocking lever from the engine.

This design gave fairly satisfactory results so long as the power output did not exceed 30-40 b.h.p. per cylinder, but when higher-powered engines were produced, considerable difficulties were experienced with this type of compressor. The volume of air to be compressed was so large, that the coolers could not cool the air well enough and not infrequently explosions occurred in the cooler coils and air supply pipes, due to ignition of oil present in the air. To overcome this defect it was suggested bv Dr. Diesel to make the compression of blast air in two stages, by by-passing the cylinder air during the compression period from the cylinder to the air compressor proper, where it was to be compressed to the blast pressure. The air from the cylinder was by-passed at a pressure of about 10 atm. (142 lbs. per square in.) into the air compressor by way of an intermediate cooler. Thus the air compressor had to compress comparatively cool air from 10 atm. to 50 atm., instead of from 1 to 50 atm. This arrangement, though it partially did away with the danger of explosion, introduced drawbacks of its own, in the shape o'f particles of dirt and carbon deposit, which were carried by the by-passing air into the compressor cylinder, often causing seizure of compressor pistons. Dr. Diesel, Professor Mayer, and the German makers, were greatly in favour of the by-pass arrangement, considering it a great improvement over the single stage compression in spite of its drawbacks, which they said were purely accidental. The Nobel engineers were, however, of a different opinion, which was based on the difficulties experienced with both systems of air compression. With the trunk piston type of engines they introduced the two-stage compound air compression proper, in which the air was compressed in two separate air compressors, driven by links from the engine. In the case of multi-cylinder engines, the L.P. and H.P. air compressors were separate units, but in single cylinder engines the air compressors formed one unit' and the two connecting rods were driven by a common link. The atmospheric air entered the L.P. stage compressor and was then compressed to T atm. (100 lbs. per square in.) then, after passing through a cooler, it entered the H.P. stage cylinder and was compressed from 7 atm. to 50-60 atm. (700-850 lbs. per square in.). Eventually on large stationary engines a three-stage compression was introduced, the compressors being all separate units, driven by links. The German Augsburg Works, soon after Nobels, also dropped the by-pass' compression and introduced two-stage, air compressors of the tandem type. As already mentioned, considerable prejudice existed among prospective customers- against Diesel engines. They were afraid of the high pressures used, and of occasional breakdowns and accidents, which were in most cases due to the inexperience of attendants. However, after some time, confidence was established, and the demand for Diesel engines in Russia became so great that the Nobel Works could not cope with the orders. Arrangements were accordingly made in the autumn of 1903 for the Kolomna Works in Golutwin to take up the manufacture of four-stroke Diesel engines under licence from Nobels, the Kolomna Works, securing, to begin with, a part of the contract for pumping sets on the Baku-Batum pipe-line. The majority of orders for Diesel engines about that time were for engines suitable for belt drive of workshops, flour mills, textile mills, and small power stations for lighting purposes, etc. The electrical engineers were at the time of the opinion that a Diesel engine could not be made to run with enough cyclic regularity to be able to drive a dynamo direct coupled to the crankshaft, and especially a direct driven alternator running in parallel with engines of other types and speed (gas, steam, water turbines, etc). To prove the fallacy of that idea, the Nobel Works installed in the power station of the Petrograd Institute of Electrical Engineers in 1905 an 80 b.h.p. twin-cylimler Diesel engine direct coupled to a D.C. dynamo, which supplied current, in parallel with steam driven dynamos, for the lighting of the premises as well as driving of various electro-motors in the laboratories and buildings. In the same year later a 400 b.h.p. three-cylinder engine direct coupled to an alternator was installed in the power house of the Perm Ordnance Works in the Ural district, and this alternator was run in parallel with an alternator driven by a steam engine. After that successful experiment the demand for high power stationary engines became very great and most of the principal provincial towns in Russia, as well as various works and shipyards, put direct-driven Diesel generators into their power houses. The largest type of four-stroke stationary engine built by Nobels was that of 200 b.h.p. per cylinder at 150 r.p.m

The cylinder dimensions of that engine were: Diameter (100 m/m. (23gin.) and stroke 800 m/m. (31^-in.). Three and four-cylinder sets of this size were built, developing 600 and 800 b.h.p. respectively. Two such 600 b.h.p. engines were installed in the steel rolling plant of Moscow Metal Works, Ltd., in 1907, one of these engines being direct coupled to the mills. Such work put very heavy stresses on the engine, as it had to work at a constantly variable load from practically 110 load to overload and vice versa. The fact that this engine has done this work already for fifteen years, only proves the reliability of the modern Diesel engine. Another interesting installation of an 800 b.h.p. engine was at the Tzaritzin Flour Mills. The engine was a four-cylinder set with a heavy flywheel pulley between the second and the third cylinders. The pulley was arranged for rope drive. The crankshaft was so designed that either pair of the cylinders could be uncoupled from the flywheel, the engine working then 011 two cylinders at lialf-power. The reason for such an arrangement was the doubt of the owners in the reliability of the Diesel engine, they preferring to have at least half the power than nothing at all in case of breakdown. It must be remembered that even a short stoppage of machinery in a flour mill entails considerable inconvenience and even loss to the millers, as most of the grain and flour in the middle of the process must he sent again from the start, and therefore the attitude of the Tzaritzin Mill owners was understandable, as to them at the time a Diesel engine installation was quite a novelty. However, it must be said to the credit of the builders of the engine that there never was an occasion to run the engine 011 two cylinders. Although the building of stationary Diesel engines formed a considerable branch of the Nobel Diesel business, it was for the designing and building of marine Diesel engines that Nobels spent most of their energies, and therefore the author will proceed to the description of a few interesting types of marine engines.

Four-Stroke Nobel-Diesel Marine Engines.

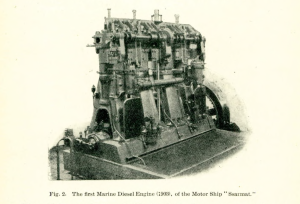

Not counting a small 20 b.h.p. French Diesel engine fitted into a small canal barge in France, it is to Nobels that belongs the credit of having built in 1903 the first marine Diesel engine and in which the speed could be varied by hand. That engine was a four-cylinder one of “A” frame trunk piston type and developed 180 b.h.p. at 240 r.p.m. The cylinder dimensions were: Diameter 320 m/m. (12fin.) and stroke 420 m/m. (16 9/ 16th in.) The outside view of the engine is shown in Fig. 2. Two such engines were fitted in 1904 into the motor-tank-ship Ssarmat, of the Nobel Bros. Petroleum Co.

The Ssarmat was a ship of 800 tons D.W. capacity and therefore of very humble dimensions as compared with present-day tankers of 15,000 tons. Her hull dimensions were: length B-P 244ft. 6 in., breadth md. 31 ft. 9in., and draught fully loaded 6 ft. She was built at the Ssormovo Shipyard, on the River Volga, and was suitable for both river and sea navigation. The engines were non-reversible and the necessary astern motion of the propeller shaft was obtained on the Del-Proposto system. That system consisted of a dynamo direct coupled to the engine crankshaft and an electromotor coupled to the propeller shaft, between those two was interposed a friction clutch. For ordinary ahead running the clutch was coupled in and the propeller was direct driven by the engine. The dynamo and electromotor were not working, but rotating simply as additional flywheels and the speed of the ship was regulated by the speed of the engine.

For astern running the clutch was released, current switched on and the electromotor turned the propeller shaft in a direction opposite to that of the engine (Fig. 3). The engine was run at constant speed, whereas the electromotor could be run at variable speed, thus regulating the speed of the ship. The Ssarmat has been in commission for nineteen years, having- still the original engines (Fig. 4). A sister ship to the Ssarmat, named Vandal, was built at the Ssormovo yard a year before the former, and was also fitted with four-stroke Diesel engines, but of the ordinary stationary type, the propeller shaft drive being purely Diesel-electric. These engines had direct coupled dynamos, which supplied current to electromotors on the propeller shafts. Three of such three cylinder engines, built by the works now owned by the New Atlas-Diesel Co., of Stockholm, were fitted into the Vandal. The cylinder dimensions

were : diameter 290 m/m. (11 7/16tlis in.) and stroke 430 m/m.

(16 15/16th ins.), each engine developing 120 b.h.p. at 240

a.p.m. The Vandal and the Ssarmat were actually the two

first motorships in the world, and, although comparatively

little publicity was given as to their performance, it must be

said that they played a very important part in the development

of motor-shipbuilding in Russia. The fact that the two

motorships in those days could maintain a regular service for

single voyages of over 3,000 miles long, year in and year out,

carrying petroleum in bulk, set many Russian shipowners

thinking, and the performance of these two ships was closely

watched. The behaviour of these two ships in service was so

satisfactory that the Nobel Bros. Petroleum Production Company

had decided then to convert the whole of their steam

fleet into motor ships. Such a conversion was probably the

biggest one ever yet undertaken, as the tonnage of the fleet was

over 650,000 tons D.W., and some of the tankers were of

10,000 tons D.W. capacity. The programme was arranged for

the gradual conversion of ships, starting with tugs and the

smaller tankers first. As the conversion could not be accomplished

by the Nobel Works alone, because they wsre very

busy with naval orders, part of the conversion work was given

over to the Kolomna Works in Golutwin, who were Nobels’

licensees. These two firms supplied the bulk of the engines

for the fleet, but a few ships were fitted with engines purchased

abroad. In many cases quite good triple expansion

steam engines had been removed and replaced by Diesels. It

was expected that by 1924 the conversion would have been

completed, but unfortunately the outbreak of the war in 1914

and of the Russian revolution in 1917, completely upset the

programme, as in 1918 the Bolsheviks had “nationalised ” the

Nobel fleet, with the result that only a comparatively small

number of old tankers are running at present. It is of interest

to note however, that of the two first marine Diesel installations,

that of the Xsarmat with Del-Proposto drive, proved to

be more reliable and economical than that of the Vandal,

which had a Diesel electric drive. The Vandal was broken up

in 1913. The replacement of steam machinery in paddle tugs

by Diesels required a considerable amount of ingenuity, as

the speed of the paddles was so much below the slowest normal

speed of Diesel engines and it naturally required the adoption

of some sort of reduction gear. It was out of the question, of course, to put slow speed land type engines, as tliey were much

too heavy and cumbersome for the weak hulls of the river

tugs. A special type of high-speed light multi-cylinder direct

reversible engine had to be designed for the purpose. In

190T such an engine was already on the test bed at the Nobel

Works and it developed 120 b.li.p. in three cylinders at

400 r.p.m. The cylinder dimensions were : diameter 275 m/m.

(10 13/16tli. ins.) and stroke 300 m/m. (11 13/16th ins.)

(Eig. 5). It was of the enclosed crankcase type with a two-

stage air compressor at the side of the engine, driven by rocking levers. This engine was the first direct reversible four-stroke Diesel engine ever built in the world. Reversing was performed through the shifting of cams by means of forks fitted to a layshaft and actuated by the liand-wheel seen in

Fig. 5 near the top of the vertical shaft. Each cylinder had two sets of cams, and to allow for their shifting, the rocking

levers of the valves had to be pressed down by means of the

long hand lever seen on the top of the engine, so as to lift the

rollers clear of the cams. This type of reverse gear is known

as Carlsund’s gear. The manoeuvring lever is seen near the

middle of the vertical shaft, and it actuated the lower lay-

sliafu, which in its turn threw the starting and fuel valves in and out of gear when necessary. The manoeuvring lever could

he rotated round a dial. The position of that lever shown in

Fig. 5 is the “ Stop ” position, when the fuel and starting

valves are out of gear. Two-stroke starting was provided, i.e.,

admission of starting air was on every downward stroke, as

otherwise with a three-cylinder four-stroke engine at certain

crank positions no starting valve may he open. Turning the

manoeuvring' lever clockwise, there came the first “ Start”

. . . . position, when the three cylinders were working on air, then

came tlie second “ Start ” position, when the first cylinder was

on fuel, and the other two 011 air, then the third “ Start ” position,

when two cylinders were on fuel and the third 011 air and

finally came the “ Work ” position when all the three cylinders

were working 011 fuel. This type of starting gear was the invention

of Mr. Nordstroem, of Nobels (Nordstroem’s patent,

Sweden, 1907). The fuel regulation could be performed in

two ways, firstly by a small hand-wheel at the lower end of

the vertical shaft, which could vary the tension of springs of

the centrifugal governor and secondly by a small hand lever,

which controlled the lift of the suction valves of the fuel

pumps. The lubrication of the engine was of three kinds:

forced for cylinders nd air compressors, by means of a

mechanical lubricator and gravity for main bearings, which

were watercooled, whereas the crankpins had banjo ring lubrication.

Two of such engines were installed in the Russian

submarine Minoga, in 1908, and it may be stated that the

above submarine, though comparatively ancient as submarines

go, did very good work during the great war. A number of

these engines were built for naval purposes as well as merchant

marine, and, in the 11011-reversible design as lighting sets in

ships and as stand-by engines in power stations. In Table I.

are given results of official 120 hour trials carried out by Professor

N. Bykoff, of Petrograd Institute of Technology upon

“Minoga” engines in 1908. This type of engine, however,

was too small and of too high a speed to work satisfactorily

in the paddle tugs, and therefore a more powerful engine of

similar design was brought out in 1908. The design of that

new engine was later standardised, and it was produced in

three, four and six cylinder models. Besides river paddle

tugs, that engine was fitted in 1909 into the Russian submarine

A Aula (three four-cylinder sets of -300 b.h.p. each at 3T5 r.p.m.)

That, engine in general appearance was similar to the

“ Minoga” engines, with the exception that in some of the later engines tandem air compressors were direct driven from

the forward end of the crankshaft. The reverse gear in that

type of engine was simplified—the shifting of cams having

been performed by a hand lever that actuated the layshaf't,

instead of by the handwheel as was on the “ Minoga ” engines.

On the later engines of the “Minoga” type the reverse gear

was also altered to hand lever cam shifting and a tandem air

compressor was fitted at the forward end of the crankshaft.

The paddle tugs had their engines placed transversely, i.e.,

parallel to the paddle shafts. In the case of larger tugs two direct reversible engines were fitted, driving the shafts through

electro-magnetic clutches. The Nobel Bros, motor tug

Ssamoyed, was a typical example of this class of river tiigs.

She was built in 1909 for service on the upper reaches of the

River Volga and Northern Canal system for the towing of oil

barges. The hull dimensions were : length B-P. 132ft. 9ins.,

breadth md. 19ft., depth md. 8ft. 3ins., draught 3ft. 3ins.,

D.W. capacity 10 tons, and Cargo towing capacity 3,200 tons.

She had two three-cvlinder reversible four-stroke engines, developing each 140 b.h.p. at 260 r.p.m., whereas the paddles

turned at 35 r.p.m. The paddle shafts were separate, each

engine driving through an electric-magnetic clutch one paddle

only, which considerably added to the manoeuvring qualities

of the tug. The necessary speed reduction was obtained

through herringbone gears of the Citroen type (Fig. 6). The

cylinder dimensions of' these engines were : diameter 330 m m.

(13ins.) and stroke 380 m/m. (15ins.). Motor tug Lesgin,

built in 1910 for the same owners, had two four cylinder engines of the above type developing 200 b.h.p. each, as the

size of the boat was larger (90 tons D.W., 4,800 tons tow% L.

175ft., B. 27ft., 1). 8ft. and draught 2ft. 4ins.). The drive

from the engines to the paddle shafts was through Dohmen-

Leblanc clutches and Citroen gears (Fig. 7). Motor tug

Ossetin (Fig. 8) of slightly smaller dimensions than the

Lesgin, was fitted also with two four-cylinder 200 b.h.p.

engines, but these were placed longitudinally side by side,

driving through Dohmen-Leblanc clutches two propeller

shafts (Fig. 9). The speed of the engines was 270 r.p.m. These

twTo larger sized tugs and their sister ships were used for towing

purposes on the lower reaches of the Volga. The first motor

tug on the Volga was the Belomor, built in 1908. She was

smaller than the above-mentioned tugs, her dimensions being:

eight tons D.W. capacity, 1,600 tons tow, L. 110ft. Gin., B. 17ft., I). 8ft., draught 3ft. 3ins. Only one reversible three-

cyliiuler engine of 140 b.h.p. was fitted, driving a paddle

shaft common to both paddles through an electric-magnetic clutch and Citroen gears. This arrangement of solid paddle

shaft had the drawback that both paddles could only be turned

in one direction at a time and therefore for the turning of the ship only the rudder was available. In 1911-1912 three

slightly larger single engine paddle tugs were built for the

service on the Vistula in Poland. They were called the Mazur,

Poliak, and Mad jar (Fig. 10). They were captured by the Germans during the war and used by them for army purposes,

upon the signing of the \ ersailles peace treaty these tugs were

returned to their rightful owners, and are now in service again.

In Fig. 11 is shown the engine of motor tug Mazur. It is interesting to note, as a special proof of the economy of the

motorship, that the Nobel Bros. Petroleum Production Company

found it cheaper to carry their oil from Baku on the

Caspian Sea to Warsaw on the Vistida, via Astrakhan, Volga,

Northern Canal System, Neva, Petrograd, Finnish Gulf, and

the Baltic Sea into Vistula, a total distance of 3,200 miles,

instead of using railways, the distance in the latter case being

only 1,900 miles. Considerable amount of trouble was experienced

at the beginning with the above mentioned Citroen type

of gear drive, the fault having been not with the gears themselves,

but with the design of the arrangement of machinery in

the ship. The hulls and engine foundations of river paddle

tugs and boats in general, were made very light as the water

surface was usually smooth and the inertia forces of slow speed

(25-40 r.p.m.) horizontal paddle steam engines were quite

negligible. With the adoption of Diesel propulsion the conditions

become quite altered, as the comparatively highspeed

vertical Diesel engine with its heavy pistons and connecting

rods was likely to set up considerable vibrations in the

foundations and in the hull, especially if the inertia forces

were not properly balanced and the period of engine vibrations

synchronised with that of the hull. Such vibrations were likely to cause deformations in the hull structure, so that the

gears could get out of alignment, sometimes with disastrous © © © 1

results. The author remembers having seen a breakdown of

such gears in one of the earlier tugs, due to the above-mentioned © © '

cause, when the teeth of the large wheel were stripped clean

off. This difficulty was eventually overcome by a suitable

design of the hull and strengthened engine foundations, combined

with a better system of' balancing of engines. It is not

the intention of the author to go into the question of engine

balancing and hull vibrations in this paper, as the subject is

too important and voluminous, and it could easily form a paper

by itself. During the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-1905 the

water communications of the Russian armies in the Far East

were very much hampered bv bands of lawless Khunghuses,

who attacked defenceless tugs and barges on the River Amour,

causing considerable delays in the delivery of supplies and

munitions. In order to bring these brigands to book the

Russian Government commandeered several river steamers and

converted them into some sort of river gunboats, bv arming

them with small naval guns and maeliins guns. These boats

helped a lot to stop looting, and even policed the river after the conclusion of war in peace time. But as these boats had

log-fired boilers and only a limited supply of wood could be

taken 011 board at a time, it was decided in 190G to build eight

new river monitors, armed with two Gin. Q.F. and four 4-Tin.

Q.F. guns, and driven by Diesel engines, which would give them

the ability of making long runs without replenishing their

fuel tanks. The total power of the engines per ship was estimated

to be 1,000 b.h.p., which was to give the ship a speed

of 11 knots. The order for all these engines was secured by

Nobels, but as the Admiralty was in a hurry to get the ships

ready as soon as possible, it was decided not to wait until the

completion of the tests of the reversible engines, but fit in

non-reversible engines with a Del-Proposto drive. Every

monitor got four engines of 250 b.h.p. each in four cylinders

running at 350 r.p.m., the engine being similar in other respects

to the tug engines of Nobel Bros. C'o. As the whole

contract of 32 engines could not be finished by Nobels in time,

a half of that number was given over to the Kolomna Works,

who built those engines from Nobels’ drawings. The hulls of

these eight monitors (known as “Shkwal” class) (Fig. 12) were built at the Baltic Shipyard in Petrograd, and were sent

in pieces to an erecting yard 011 the River Amour, where they were assembled. The first monitor, Shkwal, was ready in 1908, and after having undergone her trials in the Gulf of Finland, she was shipped in pieces to the Far East. Among the sea-going motor tankships can he mentioned Motorship Robert Nobel, of Nobel Bros. Petroleum Co. (Fig. 13. She was originally a twin-screw tank steamer of 1,700