The Silent Otto

The Silent Otto

By LYNWOOD BRYANT

The story of the gas engine that I am calling the Silent Otto—the first engine to operate on the four-stroke cycle, and the first to achieve compression of the charge within the working cylinder—has been told before.! But I should like to go over it again in order to consider a question that still seems significant to a historian interested in technology and culture: Why was this engine suddenly successful after seventy-five years of rather fumbling efforts to develop an internal-combustion engine?

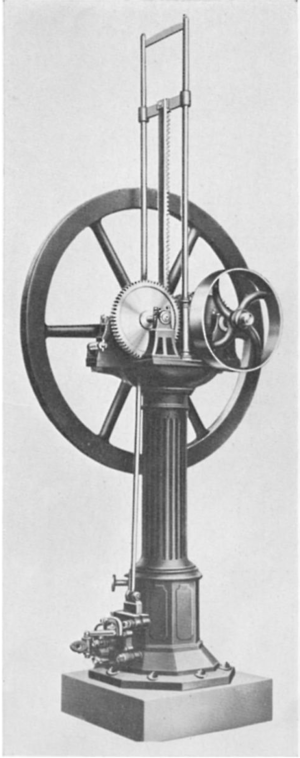

Nicolaus August Otto (1832-91) built the first Silent Otto in 1876 in the Gasmotorenfabrik Deutz near Cologne (Fig. 1). In its original form the engine had one horizontal cylinder, drew in a charge of illuminating gas and air through a slide valve, compressed it within the cylinder with a compression ratio of about 2½:1, and ignited it with a flame. The engine developed about three horsepower at a speed of 180 revolutions per minute, had a thermal efficiency of about 14 per cent (two or three times as good as a comparable steam engine), and weighed about a ton per horsepower.2 They called it “silent” not because you could not hear it when it was running—you certainly could —but because it ran much more smoothly and quietly than its immediate predecessor, the Otto and Langen, is a one-cylinder atmospheric gas Mr. Bryant is associate professor of history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. engine that crashed and clanged like a rapid-fire pile driver and must have been a difficult engine to live with. So the great selling point of Otto's engine of 1876 was that it was quiet.

In designing this engine Otto was aiming at the rapidly growing market for small stationary power plants; he needed an engine that was smaller and smoother and more flexible than the noisy and awkward Otto and Langen, and especially one that could be built for larger powers, for the atmospheric engine was limited to about three horsepower. In competition with the steam engine, the gas engine could offer superior efficiency, but it used an expensive fuel. For small powers, though, where fuel economy was not a first consideration, it had the decisive advantage of easy operation and adaptability to intermittent use. A steam engine had a long warm-up period, and its fire had to be kept going whether the engine was working or not; it had a dangerous boiler and required a full-time attendant, a license, and perhaps a separate structure to house the power plant and the fuel supply. The gas engine, on the other hand, could be started and stopped at will, it did not have to be fed when it was not working, and it could be safely installed right in a shop, with no license, no special operator, and no fuel-storage problem if it used city gas. It was advantages like these that led Otto and other heroes of the development of the internal combustion engine to dream of supplanting the steam engine.

The Silent Otto was a spectacular success. It was a sensation at the Paris Exposition of 1878, and within a few years it dominated the market for small stationary power plants. It proved to be a form of engine capable of development into many shapes and sizes, vertical and horizontal, large and small, with single and multiple cylinders, using gas or liquid fuel, and flame or hot-tube or electric ignition. Almost overnight the hot-air engine and the atmospheric gas engine were rendered obsolete, and the two-stroke engine was not a serious threat for some time. At the Paris Exposition of 1889, after the patents had been broken in Germany and France, there were said to have been fifty types of engine operating on Otto’s principle.3 At the end of the century a four-cylinder engine of one-thousand horsepower was delivered,4 and there must have been one hundred thousand engines in service bearing Otto’s name, not to mention the dozens of competing brands using the same principle, providing power for machine shops, breweries, printing presses, pumping installations, and electric-light plants.5

In order to account for the sudden success of this engine let us go back to the beginning of Otto’s work with engines, follow the course of his thought through the fifteen years of work that culminated in the Silent Otto, and try to see what the breakthrough was that led to an adequate solution to the problem that had been troubling workers on the internal-combustion engine for a generation: the problem of how to get a smooth flow of power out of an explosive fuel burned in the working cylinder.

In the 1870's and the 1880’s it was not easy to say what made the Silent Otto silent. The question was argued in great length in courts of law and in professional journals, and the most eminent experts disagreed with each other and changed their minds. Otto thought that the key to his success was a special way he had of introducing fuel and air into the cylinder that cushioned the shock of the explosion. The prevailing—but not unanimous—opinion of the profession was that he was wrong, and even today engineers do not always agree on the desirability of heterogeneous or stratified charges of the kind that Otto thought he had in his engine.

Otto was a traveling salesman without technical training in 1860 when he read in the paper an enthusiastic account of a gas engine built by a Frenchman named Etienne Lenoir (1822-1900). He arranged to have a similar small engine built by a mechanic, started tinkering with it in his spare time, and promptly ran up against the key problem that baffled everyone at that time: how to control an explosive fuel. The Lenoir engine, which was very widely discussed in the popular and the technical press in the period 1860-63, was a two-stroke, double-acting affair that looked very much like a steam engine and operated without compression. It sucked in a mixture of illuminating gas and air, ignited it by an electric spark halfway through the stroke, and used the remaining half as the power stroke. On the way back the piston was driven by a similar impulse on the other side. The publicity represented this engine as quiet and smooth running, and apparently it was when it was exhibited idling; but clearly Lenoir and his customers had trouble with rough running as soon as the engine took on a load, for Lenoir took out supplementary patents on two devices designed to cushion the shock, some sort of spring between the piston and the load, and some sort of auxiliary shock-absorbing cylinder.” He also tried injecting water into the cylinder in the hope of retarding the combustion and smoothing out the flow of power by generating steam.® Another promising approach at this time was to use some sort of burner outside the cylinder and let the burning gases flow into the cylinder like steam.?

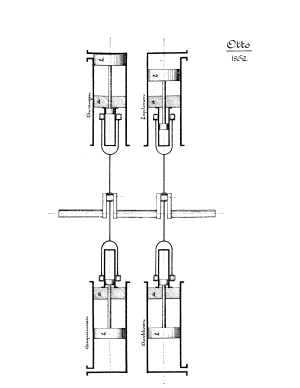

Sooner or later Otto tried all of these approaches to the problem of avoiding the destructive shocks caused by an explosive fuel. In the early sixties he worked on two experimental engines, first the one-cylinder model of the Lenoir engine and then a small four-cylinder affair with pairs of cylinders on opposite sides of a crankshaft (like today’s Volkswagen engine). Otto began work on the Lenoir model by trying all possible variations of timing, fuel-air ratio, and size of charge in an effort to find a combination that would give him a smooth-running engine. Rich mixtures ignited easily but gave heavy shocks; lean mixtures gave gentler impulses but difficulties with ignition. His problem for the next fifteen years was how to achieve both smooth burning and dependable ignition. He tried drawing in charges of various sizes before ignition—a quarter, a half, three-quarters of a cylinder full-and found, as Lenoir had, that it was best to ignite the charge halfway through the stroke. Otto later said that he also tried drawing in a full cylinder load and then compressing it on the back stroke (what else could you do with a full charge?) and found that he got a terrific explosion that drove the flywheel through several revolutions. This, he later said, was the starting point of the four-stroke cycle. I see no reason to doubt that Otto tried compressing the charge like this—it seems a perfectly natural thing to do—and undoubtedly such an experience would make a man notice the surprising increase in available energy that comes with compression. Otto also could have learned of the advantages of compression from the contemporary patents or professional journals. Schemes for compressing fuel or air or both, or for pumping them under pressure to a working cylinder, had been proposed in a number of gas-engine patents before this time. The strict Prussian patent office had in fact rejected an application involving compression on the ground that the process was already well known.! So Otto could easily have been aware of the theoretical advantages of compressing the charge before ignition, and undoubtedly he ran into the phenomenon in his experimental work in the early 1860’s. Nevertheless, it seems to me very doubtful if he had at that time any real appreciation of the value of compression as a practical working principle for an engine. In 1861 he was looking in the opposite direction, seeking ways of mitigating the severity of the shock of an explosive fuel. He had trouble enough at atmospheric pressure; it would not have made sense at that time to compress the charge if he could help it, except out of pure curiosity. One of Otto’s ideas in the early sixties was to cushion the shock by having an extra piston in the cylinder to act as a spring between the explosion and the main piston. Such an auxiliary piston he used (according to later recollections) in the small four-cylinder engine that he had built to replace the Lenoir model (Fig. 2), and a similar piston appears in his first patent application for an atmospheric engine in 1863. The extra piston had its rod fitted inside the hollow stem of the main piston, so that when the explosion occurred it would be driven against the air trapped within the main piston rod or between the two pistons.!2 Later Otto said that this piston also had the function of driving out the exhaust gases. In those days it was regarded as essential to get rid of the spent gases completely before starting a new cycle, so that the fresh charge would not be weakened by being mixed with inert gases. This requirement was very troublesome to designers, especially later when they were trying to compress the mixture within the cylinder, so troublesome that it may have been an important force in delaying the success of the four-stroke cycle. For in a four-stroke compression engine the space occupied by the compressed mixture at the end of the compression stroke, which was a rather large space in the early engines with low compression ratios, is still there at the end of the exhaust stroke, when it is occupied by unexpelled exhaust gases. One or two early compression engines drove out the exhaust by using a complicated system of rods and cranks that made the exhaust stroke longer than the compression stroke.!® Otto’s extra free piston performed this function, he thought, because on the compression stroke it was forced back into the main piston by the increasing pressure of the charge being compressed, but on the exhaust stroke it was free to move right up to the end of the cylinder and achieve complete expulsion. Anyway, Otto’s four-cylinder experimental engine was a failure, and no engineer who sees that arrangement with the four free pistons is surprised.'* At this point, Otto, baffled by the shock problem, turned off in a new direction which could have been suggested by the atmospheric steam engine or by his own experience. In his first experimental engine Otto had found that when he used a charge too small to drive the piston to the end of the cylinder, the piston would return by itself, because the gas cooled and contracted surprisingly quickly and atmospheric pressure drove the piston back. Otto turned to the atmospheric principle in 1863, and the solution he finally adopted was to use the explosion to drive a heavy piston up in a vertical cylinder without restriction and then let the gentler atmospheric pressure and the weight of the piston do the work on the way down. Otto is said to have worked out this engine by himself, but the first form of it is so close to an engine of Barsanti and Mateucci—they both even have one of those extra free drawing in the article quoted in n. 10, with minor changes to support the view that this engine used the four-stroke cycle. 13 E.g., the Atkinson engine described in Donkin, pp. 104-5, or in the Scientific American Supplement, XXVII (1889), 10929. 14] note that Frank Duryea’s first engine in America, also a failure, had a similar

free-piston arrangement to drive out exhaust and that the free piston apparently

caused loud knocks (Don H. Berkebile, “The 1893 Duryea Automobile,” United

States National Museum Bulletin 240 [Washington, D.C., 1964], pp. 10-15).

to join forces to exploit the engine, with Otto supplying the experi-

ence, machines, and patents (and some debts), and becoming the re-

sponsible managing partner, while Langen found the capital and ac-

cepted limited responsibilities and liability.

Development was slow, and the company had to be reorganized twice

in the next eight years. Each time Langen had to find more capital and

felt obliged to take a more active part in the management, and Otto’s

financial share in the business declined. For Otto the gas engine was a

full-time job, but Langen was a general entrepreneur who kept his

broad interests in Rhineland industry, in public affairs, and in the engi-

neering profession. He was also a technical man himself, trained at

Karlsruhe, interested in heat engines, already known as an inventor

when he first met Otto. He always remained close to the technical

problems of his enterprises, even after his specific management respon-

sibilities were heavy. The one-way clutch that made the Otto and

Langen engine practical, for example, was mostly his, as was also the

idea of the famous monorail rapid-transit line suspended over the

Wupper River, which is still running.

It was Langen who brought the formidable talents and statesmanship

of Franz Reuleaux (1829-1905) to bear on the affairs of the Gasmo-

torenfabrik. Langen and Reuleaux had been classmates at Karlsruhe

and fellow students of Ferdinand Redtenbacher (1809-63), the father

of the science of machine design, who in the 1850’s was preaching about

the scandalously low efficiency of the steam engine and appealing for

a scientific study of heat that would lead to a better kind of engine.

Reuleaux was a versatile, enthusiastic, and prolific man who became a

leader of the profession, an engineer of maximum distinction with a

philosophical bent and a taste for poetry, an authority on the kine-

matics of machinery, and a man with a sense of social responsibility.

To him the development of the gas engine was a part of a larger

struggle for economic democracy; by making artificial power available

to the individual craftsman and small scale industrialist, he thought, the

gas engine would give the small man a chance to recover some of the

advantage that the steam engine with its large capital requirements had

given to the large industrialist.’® Reuleaux knew everybody, went to

all the international expositions, usually as a judge, and served on in-

numerable committees. In all of these capacities he was extremely useful

to the Gasmotorenfabrik.

As soon as Langen had joined forces with Otto, Reuleaux began his

activities as consultant by inspecting Otto’s first primitive atmospheric

engine in 1864 and suggesting improvements. He was on the technical

commission of the Prussian Patent Office when the revised engine got

a patent in 1866 and on the committee of judges when it got the gold

medal at Paris in 1867. For many years thereafter Langen forwarded

to him for review all the bright ideas generated by his technical staff

in Cologne, and Reuleaux kept a stream of evaluations and suggestions

flowing back in the mail from Berlin. It was Reuleaux who made the

Gasmotorenfabrik sensitive to long-range economic and technical

trends and adaptable to the changing markets.

To these technical resources Langen also added Gottlieb Daimler

(1834-1900), who joined the Gasmotorenfabrik in 1872 as general man-

ager with the initial task of reorganizing the production facilities, and

Daimler brought along his mechanic, Wilhelm Maybach (1846-1929).

In his earlier years Daimler was primarily a production man, and in his

later years primarily a promoter, but he was an ambitious and ener-

getic technical innovator on his own account too. Ideas came easily

to him, but the best ones came from his man Maybach, who at that time

was scarcely visible behind the conspicuous figure of Daimler.?!

At the time of the birth of the Silent Otto the company thus in-

cluded five technical men whose names are still remembered: Otto, the

self-made engineer, who was generally responsible for the most impor-

tant inventions; Daimler, energetic promotor and production man;

Maybach, a machine-designer of real genius; Langen, the responsible

business man who held the firm together, which was not always easy

with the clashing temperaments of Daimler and Otto, and Reuleaux

on the side to call on for top policy and philosophy. In these years and

with these men the Gasmotorenfabrik established a research and devel-

opment tradition and policy that must have been unusual at the time.

The company was concentrating on one product—gas engines—but it

spent a great deal of energy and talent on the development of this

product and on research on new applications and forms and compo-

nents of it, some of it aimed at quite remote goals. It was a conservative

firm and continued to use gas fuel, slide valves, and flame ignition a

little longer perhaps than it should have, but it bought and studied

competing machines and developed alternative methods so that when

the time was fully ripe it was ready with its own electric ignition,

carburetors for liquid fuel, and even locomotives and Diesel engines.

So in the critical years 1875-76, when sales began to drop, the com-

pany was able to draw on an impressive array of technical talent. The

Otto and Langen engine, the sole product of the company, had been

quite successful in the market for a few years, and production facilities

recently had been expanded. The reason for the alarming decline in

sales seems to have been that the engine was inflexible and not practical

in sizes larger than about three horsepower (the average size of the

engines produced was about one horsepower) at a time when the de-

mand was increasingly for more powerful engines. The designers of

the Otto and Langen were up against this ceiling because they were

relying on atmospheric pressure, and they could not increase the diam-

eter of the cylinder without a proportional increase in the height, and

the one and one-half horsepower model already needed about twelve

feet of head room. It seemed very difficult to get two engines to work

on the same shaft, and it would be unthinkable to have two such noisy

engines in a room anyway.2

In this situation the technical men tried everything they could think

of to improve the performance or widen the market for the Otto and

Langen—noise reduction, improved transmissions, horizontal cylinders,

coupled cylinders. Langen worked on a hydraulic transmission, but

nothing came of it. Daimler tried schemes for compressing the gas, for

working on both sides of the piston, and for connecting two cylinders,

but none of his schemes worked out. Maybach came through with a

good carburetor that set the atmospheric engine free from fixed gas

systems, and so made one of the earliest gasoline engines, but it was

still subject to the same power ceiling.

The company was also exploring the possibilities of different types

of engines. Langen sent off to America for two samples of the Brayton

engine, which he had heard good things about; it avoided the problem

of shocks by having an external burner and feeding the burning gases

into the cylinder like steam. Otto had been thinking about hot-air

engines since 1871 and had already made several proposals for new

kinds of hot-air engines using gas as a fuel, with one and two cylinders,

with and without compression, double acting and single acting, direct

acting and atmospheric. Reuleaux did not think well of any of them.

In July, 1875, alarming news came in the mail from Berlin: Reuleaux

saw on the horizon a new kind of hot-air engine using compression,

which would be lighter than the Otto and Langen in the small sizes

and practical in sizes up to eight or ten horsepower. He had the satis-

faction of knowing that it was designed by an old student of his, but

it looked like dangerous competition for the Gasmotorenfabrik, and

Reuleaux called for an all-out effort. “Der Krieg ist da!” he cried. “Alle

Mann auf Deck, und das schnell.” Otto responded by reworking an

earlier proposal for a hot-air engine using compression. Reuleaux dis-

missed it quite curtly, insisting that the solution must be a gas engine

(ie., not a hot-air engine; he recognized the advantages of gasoline

as a fuel, which Maybach was working on at the time).?* But he ap-

proved of Otto’s efforts to achieve slow burning in high-pressure air.

* * *

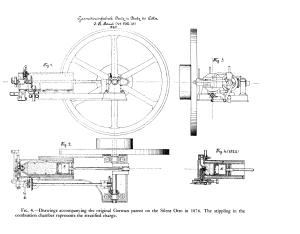

It was under this kind of pressure, in this context, with this support

from Reuleaux, that Otto turned back early in 1876 to his old idea of

compressing the mixture of fuel and air in the working cylinder. He

was still concerned about the violent explosions, but somehow he per-

suaded himself to get along without that extra shock-absorbing piston.

This time he worked out all the details of the four-stroke cycle, I sus-

pect for the first time, including a half-speed shaft to control intake,

exhaust, and ignition. And the engine ran smoothly and quietly.

Otto thought the reason for his success was the special method he

devised for mixing the gases in his cylinder that gave him what we

may call loosely a stratified charge, which made a shock-absorbing

device unnecessary because the gases themselves performed the cushion-

ing function (Fig. 4.). To Otto the essence of the invention was not

the four-stroke cycle, and not even the idea of compressing the

fuel in the cylinder—although both were mentioned incidentally in

his basic patent—but, rather, a special kind of burning that somehow

gave a gradual development of heat rather than a sudden explosion.?®

The idea came to him, Otto said, early in 1876 when he was idly

watching the smoke issuing from a factory smokestack billowing and

swirling up into the air and gradually thinning out, and he thought of

a combustible mixture entering the cylinder of an engine in this way.

The atmosphere, in his analogy of the smokestack, represented an inert

gas, and the smoke was the combustible mixture. This gave him the idea

of a rich mixture, powerful and easily ignited, which was insulated from the piston by being dispersed in an inert medium that acted as a

cushion. From this line of thinking Otto got the notion that he could

use inert gases to perform the function of that shock-absorbing piston.28

On this theory it was not necessary to be so concerned about getting

rid of exhaust gases. In fact, the retention of exhaust gases was now

transformed from a necessary evil to a positive good. Later on we

actually find Otto’s attorneys arguing that the retention of exhaust

gases is sufficient to prove infringement.

What Otto did with the engine to implement this idea was to provide

a slide valve actuated by the half-speed control shaft, which slid back

and forth across the entrance to the cylinder admitting through various

holes first pure air for about half the stroke, then a fuel-air mixture of

increasing richness. Finally, at the end of the compression stroke a flame

from an external standing burner was admitted through an ingenious

system of small passages that made it possible to get a flame into this

cylinder at a time of high pressure. What he thought he had in the

combustion chamber at the time of ignition was a layer of old exhaust

gases nearest the piston, then a layer of plain air, then a fuel-air mixture

of increasing richness, with the richest mixture nearest the point of

ignition. One might think of this as a stratified charge, on the assump-

tion that these layers would retain their relative positions during the

compression stroke, which was what Otto had been looking for in the

early sixties, a mixture rich enough at the point of ignition to ignite

dependably, but thin enough at the piston to attenuate the shock. But

it was not necessary to Otto’s theory that there be distinct layers—the

layers could shade off into each other as gradually as you please, he

said, or instead there might be just irregular streams of a combustible

mixture in an inert medium (Fig. 5).

In the long and heated arguments that followed about exactly what

was going on in Otto’s cylinder it was not always easy to grasp Otto’s

meaning, and he resisted attempts by his friends to simplify his idea.

It was not, strictly speaking, stratified layers of decreasing richness that

he claimed, nor was it a heterogeneous mixture, nor was it slow burn-

ing or delayed burning or after burning. He seems to be saying some-

thing like this: My engine runs smoothly because of the peculiar struc-

ture of the gases in the cylinder. The gases are so arranged that the

combustion is propagated from one fuel-air particle to another through

some sort of inert medium that does not participate in the combustion

but has the function of mitigating or attenuating the shock. Otto

thought he could detect this kind of burning through a pressure-volume

diagram of the kind provided by the indicator mechanism used since

the time of James Watt to give a running record of pressures within

cylinders of steam and gas engines. The indicator diagrams that Otto

took from a Lenoir engine showed a sharply oscillating and rapidly

declining pressure after ignition. Those oscillations, he said, represented

the shocks that he had been trying to eliminate. The diagram that he

took from his own engine showed a smoother and slower decline of

pressure after ignition. What I claim as my invention, Otto said in

effect, is the special structure of the gases that causes the special kind

of burning that causes this smooth and slow expansion curve on the

indicator diagram?®® (Fig. 6).

The Gasmotorenfabrik guarded its patents jealously and in the early

1880’s hunted down infringers relentlessly. The four-stroke cycle claim

fell in most countries when one of Otto’s hard-pressed competitors dug

up the extraordinary story of Alphonse Beau de Rochas?*—but this was

not the heart of Otto’s case anyway. The key issue, on which he chose

to do battle, was the stratified charge. In the final English case on the

basic patent in 1885, Dugald Clerk, the most distinguished authority on

the gas engine in England, testified that the stratified charge was a

myth. He had believed it himself at first, he said, but changed his mind

in 1881. Other experts, however, were able to show that samples taken

from various locations in the cylinder had varying fuel ratios and vary-

ing combustibility of the kind they should have had on the stratified-

charge theory, and the court sustained all of Otto’s claims.

But for Otto the decisive battle was fought in Germany, and there he

suffered a humiliating defeat in 1886. In his homeland, Otto’s strong

and numerous competitors, aggrieved by his very comprehensive

thought he could detect this kind of burning through a pressure-volume

diagram of the kind provided by the indicator mechanism used since

the time of James Watt to give a running record of pressures within

cylinders of steam and gas engines. The indicator diagrams that Otto

took from a Lenoir engine showed a sharply oscillating and rapidly

declining pressure after ignition. Those oscillations, he said, represented

the shocks that he had been trying to eliminate. The diagram that he

took from his own engine showed a smoother and slower decline of

pressure after ignition. What I claim as my invention, Otto said in

effect, is the special structure of the gases that causes the special kind

of burning that causes this smooth and slow expansion curve on the

indicator diagram?®® (Fig. 6).

The Gasmotorenfabrik guarded its patents jealously and in the early

1880’s hunted down infringers relentlessly. The four-stroke cycle claim

fell in most countries when one of Otto’s hard-pressed competitors dug

up the extraordinary story of Alphonse Beau de Rochas?*—but this was

not the heart of Otto’s case anyway. The key issue, on which he chose

to do battle, was the stratified charge. In the final English case on the

basic patent in 1885, Dugald Clerk, the most distinguished authority on

the gas engine in England, testified that the stratified charge was a

myth. He had believed it himself at first, he said, but changed his mind

in 1881. Other experts, however, were able to show that samples taken

from various locations in the cylinder had varying fuel ratios and vary-

ing combustibility of the kind they should have had on the stratified-

charge theory, and the court sustained all of Otto’s claims.

But for Otto the decisive battle was fought in Germany, and there he

suffered a humiliating defeat in 1886. In his homeland, Otto’s strong

and numerous competitors, aggrieved by his very comprehensive

It was an ironic defeat, for it was Otto himself, or his Gasmotoren-

fabrik, who insisted on the inquiry that led to his ruin,* and Otto was a

proud man, sensitive in matters of prestige and precedence. He is said to

have died an embittered man, deeply resenting this legal defeat as a re-

flection on his professional integrity, still clinging to his notion of the

stratified charge as the reason for the success of the Silent Otto. But

by the end of the century the engineering world was pretty generally

convinced that Otto was wrong, that a gas engine should have a mixture

as homogeneous as possible and as clean of exhaust gases as possible, and

that smooth running was achieved by providing the right mixture and

timing the ignition properly.3”

As we look back with our superior knowledge and ask what made the

Silent Otto silent, we can see that the omission of that extra shock-

absorbing piston is reason enough. If in his previous attempts to work

with a compressed mixture in the four-cylinder experimental engine of

1862 Otto used those free pistons, as he said he did, with their own un-

predictable movement not precisely dependent on crank angle, then he

could not time his ignition precisely, and it is no wonder that he was

faced with destructive shocks. When he came back to the idea of a

compressed mixture inside the cylinder in 1876, he came back with fif-

teen years of experience with valves and ignition and timing, and with a

new idea of a special kind of burning due to a stratified charge. This

idea may have been false—although as I shall show presently there may

have been something in it—but it led to a successful engine because it

encouraged Otto to try the engine without the free piston and to carry

through the idea of the four-stroke cycle as a method for achieving the

compression of a fuel within the cylinder, without his former worries

about destructive shocks and without feeling the need to expel exhaust

gases completely. He discovered that explosions were not a problem

and that they delivered a surprising amount of power, enough to drive

a practical engine with only one impulse every four strokes.

* * *

If this were the end of the story, we should have another case of an

inventor who was wrong but successful, and we might extract from it

the moral that good engineering can be based on bad science. But it is

not the end of the story. The fact is that Otto’s idea of the stratified

charge keeps reappearing, and historians loyal to the memory of Otto

can take considerable comfort in the revival of interest in his favorite

idea that has taken place in recent years. The very phrase “stratified

charge,” which caused Otto so much trouble, is now appearing again in

the literature.

In 1922 Sir Harry Ricardo (1885——) re-invented the stratified

charge: he proposed igniting an especially rich mixture in a bulbous

~~ antechamber so that a flame would shoot out into the main combustion

chamber and there set fire to a mixture so lean that otherwise it would

not burn at all.38 This is exactly the same idea that Otto had when he

provided a long, narrow passage as entrance to his combustion chamber

during the first months of his work on the Silent Otto: It was sup-

posed to contain the richest part of the mixture and to generate a flame

to shoot out into the main charge? In the following years Ricardo’s

idea was used in various engines, especially Diesel engines; and recently

the stratified-charge idea has been applied in various ways to spark-

ignition engines.

A dozen experimental programs’ are now in progress, trying new

cylinder shapes and modifications of fuel and ignition systems in an

attempt to achieve fuel economy through more complete combustion or

the use of leaner mixtures or cheaper fuels. They all involve some sort

of separation of the rich and lean mixtures, with the rich mixture con-

centrated near the point of ignition. Two of the best known of these

current experimental projects are the Texaco Combustion Process! and

the Witsky process,*? both of which involve direct injection of uncar-

bureted fuel into a swirl of air, one with the swirl and one against it.

The Russians also have their version of the stratified charge, the Nilov

Ignition Engine, which has two carburetors, one of which provides a

lean mixture near the piston, and the other a rich mixture for a small

antechamber containing a spark plug.

One advantage claimed by the Texaco Combustion Process that

would have been especially interesting to Otto is that it eliminates

knock, presumably by achieving such a concentration of fuel at the

point of ignition that there is not enough left in the remoter parts of the

cylinder to be detonated by self-ignition; in fact, this engine is said not

to have a flame front moving down the cylinder at all but something

more like a steady flame burning at one location.** It was a different sort

of shock that troubled Otto, of course—he probably did not try a high

enough compression to run across the phenomenon of combustion

knock as we know it, but it is interesting to see that he had the same sort

of need to control the combustion within his cylinder and that he tried

to control it in the same way, by concentrating a rich mixture near the

point of ignition.

Another parallel with the Otto story is that again the engineering

Establishment tends to be skeptical of the rather enthusiastic claims of

some of the men now working on the stratified charge. No such engines

have yet been produced that run reliably and economically over a

wide enough range of conditions to be commercially interesting. But

if the ideas are wrong, they are still seductive; and such respectable

firms as the Texas Oil Company and the Ford Motor Company can still

justify the investment of millions of dollars in research on the idea Otto

once regarded as his own, the stratified charge.

Reference

- Recently, e.g. by Gustav Goldbeck in “Entwicklungsstufen des Verbrennungsmotors,” Motortechnische Zeitschrift, XXIII (1962), 76-80, and in several other articles; by Friedrich Sass in Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaues von 1860 bis 1918 (Berlin, 1962), pp. 19-74, 147-67; and by Arnold Langen in Nicolaus August Otto, der Schopfer des Verbrennungsmotors (Stuttgart, 1949). I rely heavily on Professor Sass for information about engines. I also acknowledge very helpful conversations with Dr. Goldbeck, archivist of Klockner-Humboldt-Deutz, and with Professors C. Fayette Taylor and Augustus R. Rogowski of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Sass, p. 44; Paul Gille, “Beau de Rochas. Les trois mémoires de 1862 sur différentes conditions d’application de Iénergie,” Documents pour Pbistoire des techniques, No. 2, p. 37; Conrad Matschoss, Geschichte der Gasmotorenfabrik Deutz (Berlin, 1921), p. 55.

- Gustav Goldbeck, “Nicolas-Auguste Otto (1832-1881),” Documents pour Ibistoire des techniques, No. 1, p. 38. The year of Otto’s death is misprinted in this title. It should be 1891.

- Sass, p. 319.

- Matschoss, pp. 107-8.

- For an early popular account see Alfred Darcel, “Un nouveau Moteur,” L’Dlustration, XXXV (1860), 342-43. For a technical study see H. Tresca, “Procés-Verbal des expériences faites sur les moteurs a gaz de M. Lenoir,” Annales du Conservatoire Impérial des Arts et Métiers, 1 (1861), 849-79. Articles by engineers appearing in German journals that Otto could have seen are conveniently summarized under the heading “Gaskraftmaschine” in Jabresbericht iiber die Fortschritte der mechanischen Technik und Technologie, 1 (1863), 111-31. “According to Cosmos, and other French papers,” said the Scientific American (III [1860], 193), “the age of steam is ended—Watt and Fulton will soon be forgotten. This is the way they do such things in France.”

- Goldbeck, “Entwicklungsstufen des Verbrennungsmotors,” p. 78.

- Henry Henderson, “The Use of Water and Steam in Internal-Combustion Engines,” Cassier’s Magazine, XXXIII (1907), 381-89.

- This was the principle of the Brayton engine patented in the United States in 1872, described in Bryan Donkin, 4 Text-Book on Gas, Oil, and Air Engines (London, 1894), pp. 51, 289-92. George B. Selden imitated this engine in his famous automobile patent of 1879.

- Eugen Langen, Vortrag des Herrn Kommmerzienrat Eugen Langen gebalten in der Sitzung des Kilner Bezirksvereins deutscher Ingemieure am 2. Mirz 1886 uber das Urteil des Reichgerichtes vom 30. Januar 1886 betreffend die Patente der Gasmotorenfabrik Deutz (Cologne, 1886) ; Arnold Langen, pp. 25-29; Kurt Schnauffer, “Nicolaus August Ottos Vierzylinder-Viertakt Motor von 1861. Zum 100 jahrigen Jubilium des Viertaktverfahrens,” Motortechnische Zeitschrift XXIII (1962), 1-4. Otto's experimental work of the early 1860’s is referred to in a few contemporary letters but is described only in his testimony in patent litigation about twenty years later and in his unpublished reminiscences written in 1889, parts of which are quoted in Sass and in the biographical work of Arnold Langen and Goldbeck already cited. The engines themselves do not survive, and there are no contemporary drawings.

- Gustav Goldbeck, “Nicolas-Auguste Otto,” p. 38. An example of a technical article that Otto could have seen specifically recommending compression is Gustav Schmidt, “Theorie der Lenoir’ schen Gasmachine,” [Dingler’s] Polytechnisches Journal, CLX (1861), 321-37. The Million engine using compression patented in England in 1861 is fully described and illustrated in Polytechnisches Journal, CLXXIX (1866), 329-40.

- Sass, pp. 23-24; Eugen Langen, pp. 2-3. A drawing of this engine made in 1885 for use in patent litigation is reproduced in Sass, p. 23. Schnauffer uses the same drawing in the article quoted in n. 10, with minor changes to support the view that this engine used the four-stroke cycle.

- E.g., the Atkinson engine described in Donkin, pp. 104-5, or in the Scientific American Supplement, XXVII (1889), 10929.

- I note that Frank Duryea’s first engine in America, also a failure, had a similar free-piston arrangement to drive out exhaust and that the free piston apparently caused loud knocks (Don H. Berkebile, “The 1893 Duryea Automobile,” United States National Museum Bulletin 240 [Washington, D.C., 1964], pp. 10-15).

43 Schweitzer and Grunder, p. 547; Motortechnische Zeitschrift, XXIV (1963), 30.

44 Barber et al., pp. 28-29.