Boat engine construction in Germany (Article): Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

The research into the history of boat engine construction on the German coasts must be described as unsatisfactory. For the southern Baltic coast region, only the two preliminary studies by Rudolph (1989, 1994) and the Faaborg company chronicle of the Callesen company (1989) are available; for the North Sea coast - in the broadest sense - there is Kaiser's chronicle of the Bergedorfer Motorenwerke (1977) and Vicco Meyer's engine chapter in Karring's description of the motor sailboats built by the Germaniawerft (1987). This situation is surprising, since the literary and archival source situation is not bad: there are sufficient contemporary reports and descriptions from the early days of development. For the period before 1945, researchers also have access to the "Communications of the German Sea Fishing Association", the "German Fish Industry", the "German Reich Address Book for Industry, Trade and Commerce" and the "Handbook of German Joint Stock Companies", as well as the annual reports of the regional Chambers of Industry and Commerce, the local address and telephone books, and finally the entries in the local commercial registers, as well as patent documents and the German trademark register. Competent contemporary witnesses from most of the companies in question are still alive. The boat engines preserved in museums form a third, if not overly extensive, category of sources, which unfortunately only covers part of the coastal area. | The research into the history of boat engine construction on the German coasts must be described as unsatisfactory. For the southern Baltic coast region, only the two preliminary studies by Rudolph (1989, 1994) and the Faaborg company chronicle of the Callesen company (1989) are available; for the North Sea coast - in the broadest sense - there is Kaiser's chronicle of the Bergedorfer Motorenwerke (1977) and Vicco Meyer's engine chapter in Karring's description of the motor sailboats built by the Germaniawerft (1987). This situation is surprising, since the literary and archival source situation is not bad: there are sufficient contemporary reports and descriptions from the early days of development. For the period before 1945, researchers also have access to the "Communications of the German Sea Fishing Association", the "German Fish Industry", the "German Reich Address Book for Industry, Trade and Commerce" and the "Handbook of German Joint Stock Companies", as well as the annual reports of the regional Chambers of Industry and Commerce, the local address and telephone books, and finally the entries in the local commercial registers, as well as patent documents and the German trademark register. Competent contemporary witnesses from most of the companies in question are still alive. The boat engines preserved in museums form a third, if not overly extensive, category of sources, which unfortunately only covers part of the coastal area. | ||

== Technical definitions == | |||

In order to provide definitional clarity regarding the variety of engine technologies used in the early phase of boat motorization and which are no longer generally known today, | In order to provide definitional clarity regarding the variety of engine technologies used in the early phase of boat motorization and which are no longer generally known today, | ||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

During the first two decades of the 20th century, people were keen to experiment in the design of engine controllers, just as engineers had been in the middle of the 19th century when regulating early high-speed steam engines. Two types of controller were mainly used for hot-bulb engines, which differ in their operating principle: In the vertical centrifugal controller, which can be traced back to James Watt, the centrifugal force of rotating flywheels worked against gravity, while in the more recent axle controllers, which were derived from an invention by Charles Brown (1862), the centrifugal force of horizontally mounted rotating flywheels, but braked by springs, produced the desired effect. The control elements of these controllers show a certain range of variation: Rotary eccentrics, stepped cams, inclined cams or hanging wedges were used, which drive the fuel pump pistons in different ways. As far as the mechanics used are known, they are mentioned here, in the assumption that such design variations could be of indicative value for the regional technological history of development. | During the first two decades of the 20th century, people were keen to experiment in the design of engine controllers, just as engineers had been in the middle of the 19th century when regulating early high-speed steam engines. Two types of controller were mainly used for hot-bulb engines, which differ in their operating principle: In the vertical centrifugal controller, which can be traced back to James Watt, the centrifugal force of rotating flywheels worked against gravity, while in the more recent axle controllers, which were derived from an invention by Charles Brown (1862), the centrifugal force of horizontally mounted rotating flywheels, but braked by springs, produced the desired effect. The control elements of these controllers show a certain range of variation: Rotary eccentrics, stepped cams, inclined cams or hanging wedges were used, which drive the fuel pump pistons in different ways. As far as the mechanics used are known, they are mentioned here, in the assumption that such design variations could be of indicative value for the regional technological history of development. | ||

== History of the development of motorization of boats on the German Baltic coast. == | |||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

In 1928, the second list of fishing boat engines eligible for Reich loans in Germany still listed 14 glow-bulb engine manufacturers in addition to seven diesel manufacturers.3 In 1935, the 7 hp small diesel (with horizontal cylinder) from Deutz became eligible for Reich loans. In 1936, Junkers advertised its (vertical) single-cylinder double-piston engine with 12 hp for the first time in Chemnitz. In 1939, the most frequently used diesel engine brands for Baltic fishing cutters were: Buckau Wolf (Magdeburg), Deutsche Werke (Kiel), Hanseatic Motoren-Gesellschaft (Bergedorf), Klöckner-Humboldt-Deutz (Cologne), Krupp-MODAAG (Darmstadt), MAN (Augsburg and Nuremberg) and MW M (Mannheim), - for open beach boats: Deutz and Junkers. In 1958, ten of the private cutters based in Sassnitz on Rügen had a hot-plug engine and 21 had a diesel engine. In 1958, the ratio of hot-plug to diesel engines for the (private) freight vessels operating on the Pomeranian lagoons and harbors was 51:30, plus three Brons engines. In 1968, a brand-new hot-plug engine (from the Swedish manufacturer Bolinder) was installed in a cutter on the German Baltic coast in Lauterbach on Rügen for the last time. Of the hot-plug engines from the early phase of this development, the only one still in operation as a drive for a fishing vessel is the 25 hp engine from the Kiel manufacturer Neufeldt & Kuhnke in the Fehmarn cutter ORT 2. | In 1928, the second list of fishing boat engines eligible for Reich loans in Germany still listed 14 glow-bulb engine manufacturers in addition to seven diesel manufacturers.3 In 1935, the 7 hp small diesel (with horizontal cylinder) from Deutz became eligible for Reich loans. In 1936, Junkers advertised its (vertical) single-cylinder double-piston engine with 12 hp for the first time in Chemnitz. In 1939, the most frequently used diesel engine brands for Baltic fishing cutters were: Buckau Wolf (Magdeburg), Deutsche Werke (Kiel), Hanseatic Motoren-Gesellschaft (Bergedorf), Klöckner-Humboldt-Deutz (Cologne), Krupp-MODAAG (Darmstadt), MAN (Augsburg and Nuremberg) and MW M (Mannheim), - for open beach boats: Deutz and Junkers. In 1958, ten of the private cutters based in Sassnitz on Rügen had a hot-plug engine and 21 had a diesel engine. In 1958, the ratio of hot-plug to diesel engines for the (private) freight vessels operating on the Pomeranian lagoons and harbors was 51:30, plus three Brons engines. In 1968, a brand-new hot-plug engine (from the Swedish manufacturer Bolinder) was installed in a cutter on the German Baltic coast in Lauterbach on Rügen for the last time. Of the hot-plug engines from the early phase of this development, the only one still in operation as a drive for a fishing vessel is the 25 hp engine from the Kiel manufacturer Neufeldt & Kuhnke in the Fehmarn cutter ORT 2. | ||

== Periodization == | |||

The beginning of the development of boat engine construction on the Baltic coast of Germany was marked by the group of "old masters", all of whom were based in Schleswig-Holstein: | The beginning of the development of boat engine construction on the Baltic coast of Germany was marked by the group of "old masters", all of whom were based in Schleswig-Holstein: | ||

| Line 117: | Line 117: | ||

Eduard Seiler in Danzig and Hansen & Simon in Gravenstein. The possibility that there were other, as yet unknown, production facilities of this type here and there on the German Baltic coast cannot be ruled out, however. | Eduard Seiler in Danzig and Hansen & Simon in Gravenstein. The possibility that there were other, as yet unknown, production facilities of this type here and there on the German Baltic coast cannot be ruled out, however. | ||

== The manufacturing companies == | |||

Arranged according to the coastline, the manufacturers are mentioned here at the production sites with their dates of birth and training, as well as the duration of boat engine production, information on engine types and special features of production (e.g. suppliers), and finally by-products of production as well as information on the customer base and sales advertising. The lack of corresponding information means that no facts could be found out about this. | Arranged according to the coastline, the manufacturers are mentioned here at the production sites with their dates of birth and training, as well as the duration of boat engine production, information on engine types and special features of production (e.g. suppliers), and finally by-products of production as well as information on the customer base and sales advertising. The lack of corresponding information means that no facts could be found out about this. | ||

| Line 144: | Line 144: | ||

Hot-plug engines from Friedrichson were very popular in the German fishing industry and with our coastal fishermen. In 1958, out of a total of 51 ship engines, three 18 hp and eight 36 hp Dütsche Werke engines were still in use on the Pomeranian lagoon and Bodden waters. There is no information about the customers of the outboard engines: were they sports sailors, were they recreational fishermen? A 18 hp Friedrichson hot-plug engine, which comes from an Eibever, is in the Lauenburg Inland Shipping Museum; a 24 hp two-cylinder hot-plug engine salvaged from the wreck of a Rügen passenger ship in the Mönchgut Museum in Göhren on Rügen was demolished in important components by amateur handling. The Kiel Ship Museum preserves a 240 hp Deutsche Werke 6-cylinder four-stroke diesel engine delivered in 1943. The factory, which was again largely integrated into armaments production during the Second World War, was renamed HOLMAG in 1945, then MaK in 1948 and still exists today. | Hot-plug engines from Friedrichson were very popular in the German fishing industry and with our coastal fishermen. In 1958, out of a total of 51 ship engines, three 18 hp and eight 36 hp Dütsche Werke engines were still in use on the Pomeranian lagoon and Bodden waters. There is no information about the customers of the outboard engines: were they sports sailors, were they recreational fishermen? A 18 hp Friedrichson hot-plug engine, which comes from an Eibever, is in the Lauenburg Inland Shipping Museum; a 24 hp two-cylinder hot-plug engine salvaged from the wreck of a Rügen passenger ship in the Mönchgut Museum in Göhren on Rügen was demolished in important components by amateur handling. The Kiel Ship Museum preserves a 240 hp Deutsche Werke 6-cylinder four-stroke diesel engine delivered in 1943. The factory, which was again largely integrated into armaments production during the Second World War, was renamed HOLMAG in 1945, then MaK in 1948 and still exists today. | ||

==== Kiel ==== | |||

Carl Daevel (1848 Niewohld Kr. Plön -1908 Kiel), trained as an engineer, bought the Kiel machine factory of Sievers & Weyhe on Kirchhofallee in 1880 and built there - initially with 30 employees, by 1900 with over 120 - high-speed steam engines (to drive dynamos) as well as traction engines and pumps. In 1888 he was granted a patent for a ship's screw propeller with adjustable blades. In 1890, the annual report of the Kiel Chamber of Industry and Commerce for Daevel's factory on Kirchhofallee mentioned for the first time the construction of gas and petroleum engines. From 1898 the company was known as "Kieler Maschinenbau AG, formerly Daevek". In those years the German Sea Fishing Association tried to interest a medium-sized company in the construction of simple, robust and reliable boat engines in the style of the Danish hot-head engines. In the winter of 1904, thanks to the intervention of the engineer Duge in Kiel, Kiefer Maschinenbau AG, formerly Daevel, was able to get the company to look into the construction of a fishing engine. The factory's engineers were repeatedly shown the "Alpha" system engines and demonstrated them in operation, and were also informed of all the experiences made with the engines to date... The Daevel engine has been in operation since March 1905. 7 | |||

This was a two-cylinder four-stroke glow-head engine of 8 hp, which was later described in great detail by Romberg.8 Nothing is known about the manufacturing conditions, however: one can assume, however, that all the gray, malleable and colored cast iron parts, as well as the lubricating device, were manufactured in the Daevel factory itself; certainly also the Daevel regulator: the front journal of the crankshaft drove a horizontal control shaft, offset in height and laterally, via two gear wheels, on the rear end of which sat a rotating open housing for two spring-braked flywheel weights housed in it. The centrifugal movement of these weights was transferred by angle levers and joints through recesses in the housing wall to the front of the regulator, where the angle levers could move a sleeve-shaped sliding sleeve to the right or left. A stepped cam sat on the sleeve, which controlled the movements of the vertically operating fuel pump piston. This type was later adopted or modified by Jörgensen and the Deutsche Werke, but also in Laboe, Greifswald, Saßnitz and Freest. | |||

Latest revision as of 13:47, 29 January 2025

BOAT ENGINE CONSTRUCTION IN GERMANY

COASTAL AREA (UNTIL 1945)

PART 1: THE BALTIC SEA REGION

BY WOLFGANG RUDOLPH

On the current state of research

The research into the history of boat engine construction on the German coasts must be described as unsatisfactory. For the southern Baltic coast region, only the two preliminary studies by Rudolph (1989, 1994) and the Faaborg company chronicle of the Callesen company (1989) are available; for the North Sea coast - in the broadest sense - there is Kaiser's chronicle of the Bergedorfer Motorenwerke (1977) and Vicco Meyer's engine chapter in Karring's description of the motor sailboats built by the Germaniawerft (1987). This situation is surprising, since the literary and archival source situation is not bad: there are sufficient contemporary reports and descriptions from the early days of development. For the period before 1945, researchers also have access to the "Communications of the German Sea Fishing Association", the "German Fish Industry", the "German Reich Address Book for Industry, Trade and Commerce" and the "Handbook of German Joint Stock Companies", as well as the annual reports of the regional Chambers of Industry and Commerce, the local address and telephone books, and finally the entries in the local commercial registers, as well as patent documents and the German trademark register. Competent contemporary witnesses from most of the companies in question are still alive. The boat engines preserved in museums form a third, if not overly extensive, category of sources, which unfortunately only covers part of the coastal area.

Technical definitions

In order to provide definitional clarity regarding the variety of engine technologies used in the early phase of boat motorization and which are no longer generally known today,

In order to ensure a clear understanding of the different technologies, some definitions should be given here.

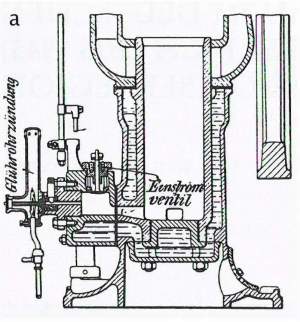

Petroleum engine: Petroleum-powered low-pressure engine with external ignition of the fuel mixture in an evaporator capsule, which is kept glowing by a permanently burning Bunsen lamp (Figure 1 A).

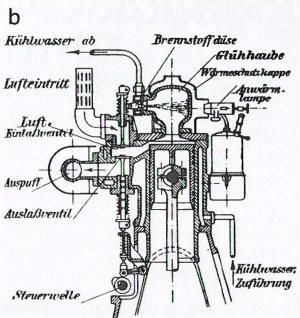

Glow plug engine: Crude oil-powered engine operating in the lower medium pressure range with external ignition of the mixture on a cast-iron glow plug on the cylinder cover, which is only heated to a brown glow by means of a heating lamp when the engine is started (Figure 1 B ).

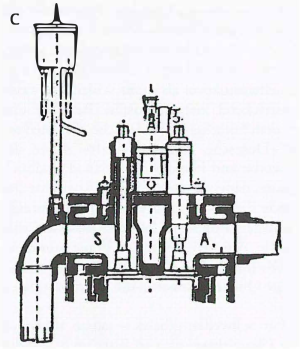

Brons engine: Crude oil-powered medium-pressure engine with self-ignition of the mixture in a special heater capsule that is firmly integrated into the cylinder head (Figure 1 C).

Figure 1

a) Petroleum engine,

b) Glow plug engine,

c) Brons engine.

(From: Kirschke, Alfred: The Gas Power Machine, B. I, II. Berlin/Leipzig 1911, 1913)

The characteristics of the Otto engine (petrol-powered low-pressure engine with external ignition of the carburetor mixture by electric spark) are probably well known. and the diesel engine (crude oil-powered medium and high pressure engine with self-ignition of the compressed mixture in the cylinder head or in a cylinder pre-chamber).

From the point of view of the folklorist, who also researches the components of the experience of practitioners and the creativity of craftsmanship for the era of special industrialization under discussion, several engine parts offer themselves as indicators: namely the design of the cooling water inlet and the air intake flaps on the crankcase, as well as the shape of the screwed-on glow plugs and the type of regulator. The early engine builders experimented very eagerly with these parts. In our region, there were at least four variants in the shape of the glow plugs: tall cylindrical "hats" (with or without a narrowed neck), hemispherical "hoods" (with or without a protruding ignition pin), flat hoods that resembled a mushroom cap, and solid balls on truncated cones.

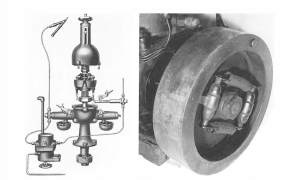

Figure 2 Left: Encapsulated centrifugal governor. Schematic representation from an operating manual for Callesen engines, Aabenraa (mid-1920s). (All photos in this article by W Rudolph, all historical representations from the author's archive, unless otherwise stated). - Figure 3 Right: Axle governor in the flywheel of the Paeschke engine, Freest (Cultural History Museum Stralsund)

During the first two decades of the 20th century, people were keen to experiment in the design of engine controllers, just as engineers had been in the middle of the 19th century when regulating early high-speed steam engines. Two types of controller were mainly used for hot-bulb engines, which differ in their operating principle: In the vertical centrifugal controller, which can be traced back to James Watt, the centrifugal force of rotating flywheels worked against gravity, while in the more recent axle controllers, which were derived from an invention by Charles Brown (1862), the centrifugal force of horizontally mounted rotating flywheels, but braked by springs, produced the desired effect. The control elements of these controllers show a certain range of variation: Rotary eccentrics, stepped cams, inclined cams or hanging wedges were used, which drive the fuel pump pistons in different ways. As far as the mechanics used are known, they are mentioned here, in the assumption that such design variations could be of indicative value for the regional technological history of development.

History of the development of motorization of boats on the German Baltic coast.

Previously presented information on the development of motorization of fishing vessels and small cargo sailing ships on the coast between North Schleswig and East Prussia can now be supplemented and clarified by more recent research results, so that it is possible to provide a reliable chronology and a periodization. Key data worth knowing are:

In 1902 Fishermen from Kiel-Möltenort were the first to install a hot-bulb engine (Danish made) in one of their boats. Fishermen from Eckernförde followed suit in 1903, and later from Maasholm in Schleswig, as well as cutter fishermen from Kolberg and Rügenwalde in Pomerania and from Memel and Pillau in East Prussia (Mitt. German Sea Fishing Association 1903 to 1905).

In 1904, Daevel in Kiel and Callesen in Aabenraa built hot-bulb engines for the first time - also for installation in boats.

In 1907 there were 44 motorboats on the German Baltic coast in the fisheries of Schleswig-Holstein, 3 in Lübeck, 1 in Mecklenburg, 19 in Pomerania, 10 in West and East Prussia (Mitt. Deutscher Seefischereiverein 1907).

In 1909, the first freight ship was equipped with an engine in Tolkemit on the Frisches Haff.

In 1910, Wilhelm Scheel in Kubitz on Rügen was the first Pomeranian freighter to install a Swedish hot-bulb engine (Skandia brand) in his new yacht SCHWALBE.

For the years before the First World War, clarity can only be brought to the confusion of contemporary names regarding the types of engines used at that time if technical drawings or photos are included in the reports and articles. Petroleum engines - in the true sense of the word - were occasionally installed as boat engines before 1900. However, they proved unsuitable for use on ships due to the permanent use of an open heating flame. The Danish hot-head engines, manufactured since 1894, finally provided a solution to the problem of a "safety engine" - as it was called at the time - for fishing and small boating. In 1906, the Kiel-based Daevel company said that the petroleum boat engines we had recently started producing were being well received. The addition of "recently" was apparently intended to indicate that these machines were a different type than the previously produced "gas and petroleum engines" that Daevel had been building since 1891: namely, hot-head engines based on the Danish model. A photo from 1905 and the accompanying technical drawings prove this. In 1911, Daevel was already talking about "oil engines", while Dittmer was still calling them "hot-head petroleum engines". As in Kiel, it seems that it was also in Apenrade, where Callesen and Bastiansen initially manufactured gas and petroleum engines, but a short time later also manufactured hot-head engines.²

Although the hot-plug engines had been significantly improved by the introduction of the two-stroke process - in Sweden at Bolinder as early as 1904, a little later in Denmark at Tuxham and Vølund, and on the German coast from 1910 - this type of engine gradually lost its once outstanding importance for driving fishing boats and small cargo sailing ships after the First World War. In the meantime, developments at Benz, Deutz and other companies had succeeded in significantly improving the usability of small diesel engines, namely by moving the self-ignition to a "prechamber" of the cylinder head or by airless direct injection, under starter with saltpeter below, which had to be inserted into the cylinder head.

In 1928, the second list of fishing boat engines eligible for Reich loans in Germany still listed 14 glow-bulb engine manufacturers in addition to seven diesel manufacturers.3 In 1935, the 7 hp small diesel (with horizontal cylinder) from Deutz became eligible for Reich loans. In 1936, Junkers advertised its (vertical) single-cylinder double-piston engine with 12 hp for the first time in Chemnitz. In 1939, the most frequently used diesel engine brands for Baltic fishing cutters were: Buckau Wolf (Magdeburg), Deutsche Werke (Kiel), Hanseatic Motoren-Gesellschaft (Bergedorf), Klöckner-Humboldt-Deutz (Cologne), Krupp-MODAAG (Darmstadt), MAN (Augsburg and Nuremberg) and MW M (Mannheim), - for open beach boats: Deutz and Junkers. In 1958, ten of the private cutters based in Sassnitz on Rügen had a hot-plug engine and 21 had a diesel engine. In 1958, the ratio of hot-plug to diesel engines for the (private) freight vessels operating on the Pomeranian lagoons and harbors was 51:30, plus three Brons engines. In 1968, a brand-new hot-plug engine (from the Swedish manufacturer Bolinder) was installed in a cutter on the German Baltic coast in Lauterbach on Rügen for the last time. Of the hot-plug engines from the early phase of this development, the only one still in operation as a drive for a fishing vessel is the 25 hp engine from the Kiel manufacturer Neufeldt & Kuhnke in the Fehmarn cutter ORT 2.

Periodization

The beginning of the development of boat engine construction on the Baltic coast of Germany was marked by the group of "old masters", all of whom were based in Schleswig-Holstein:

Callesen in Apenrade (boat engines since around 1904)

Daevel in Kiel (1904)

Christiani/Jörgensen in Kiel (1909). (4)

After a war-related interruption and after the very creatively managed changeover from armaments to peacetime production, new manufacturing companies quickly appeared:

Rehbehn in Eckernförde (1920)

Deutsche Werke Kiel-Friedrichsort (1919)

Neufeldt & Kuhnke in Kiel (1920)

Poppe in Kiel (1920)

Schulze in Kiel (1923)

Bohn & Kähler in Kiel (1920)

Bauer in Laboe (around 1920)

Lehne in Lübeck (1918)

Borowski in Kalberg (19 19)

Stolpmünder Maschinenfabrik ( 1919)

Königsberger Motorenfabrik (1918).

A third group, which became apparent from the mid-1920s onwards, could then be described as “niche occupiers” in connection with specific local developments:

Jäger in Lübeck (1929)

Greifswalder Maschinenfabrik (1925)

Funk in Saßnitz (1928)

Paeschke in Freest ( 1928)

Horn in Walgast (1931). (5)

At the end of this list is the last initiator who attempted to master a local emergency situation after the Second World War:

Koldevitz in Gag er on Rügen (1946).

In the area under investigation between North Schleswig and East Prussia, 22 medium-sized engine factories have been identified to date. In addition to those mentioned above, there are two companies in which there was probably only short-term engine production:

Eduard Seiler in Danzig and Hansen & Simon in Gravenstein. The possibility that there were other, as yet unknown, production facilities of this type here and there on the German Baltic coast cannot be ruled out, however.

The manufacturing companies

Arranged according to the coastline, the manufacturers are mentioned here at the production sites with their dates of birth and training, as well as the duration of boat engine production, information on engine types and special features of production (e.g. suppliers), and finally by-products of production as well as information on the customer base and sales advertising. The lack of corresponding information means that no facts could be found out about this.

Apenrade/ Aabenraa

Heinrich Callesen (1873 Apenrade -1931 Flensburg) was the son of an Apenrade master builder. In 1887 he began his apprenticeship in his hometown: with Boy Bastiansen, in whose machine factory steam engines, agricultural machines and woodworking equipment as well as petroleum and gas engines were manufactured. After completing his apprenticeship, Heinrich Callesen spent a long period of time on board steamships as a machine assistant. From 1895 to 1897 he studied at the Municipal Technical College for Mechanical Engineering in Einbeck. In 1899 he set up his own business in Apenrade - with 13 employees. In 1904 his first petroleum engine was built, in 1909 he developed his first hot-head engine: a two-stroke engine with 8 hp, which was soon followed by series, with outputs of up to 200 hp and increasingly tailored to installation in fishing vessels and cargo sailing ships on small coastal routes. Callesen obtained the gray cast iron and the malleable cast iron from a Flensburg foundry, the crankshaft blanks from a SiemensMartin steel forge, the location of which could no longer be determined. Red cast iron and white cast iron were manufactured in-house. The lubricators were also initially built in-house, before switching to the installation of Bosch oilers in 1919. The older Callesen engines were powered by eccentric-driven intermittent regulators with Pendulum hammers were used. Later, there were standing centrifugal regulators with encapsulated flyweights.

At higher speeds, these pulled up a sleeve with a hanging wedge on the regulator shaft. A cam disk rotated under the sleeve against the wedge cutting edge and thus controlled the drive of the horizontally operating fuel pump piston. Early on, in 1911, this Apenrade two-stroke glow-head engine received the coveted quality certificate "tested by the German Sea Fishing Association in Berlin and approved for Reich loans". Callesen was already advertising its products at that time, and the company successfully sold its engines as far as Norway and the Netherlands, as far as Pomerania and East Prussia. After 1920, Heinrich Callesen secured the German sales market, which from then on belonged to foreign countries, by granting a complete license to the "Hanseatic Motor Company" (HMG) in Bergedorf near Hamburg, whose owner, Robert Puls in Apenrade, had become a partner. His son Erich was married to one of Heinrich Callesen's daughters. The Callesen factory attempted to compensate for the drop in sales at the time by expanding its product range to include capstans, net winches, pumps, generator sets, tractors and other agricultural machines, as well as by increasing exports, for example to Poland and Turkey. In the mid-1920s, 35 employees worked at the factory.

In 1924, Heinrich Callesen began developing his own diesel engines, but it was not until 1937 that his son Peter (1911-1986) got the first Apenrade compressorless two-stroke diesel with direct injection (25 hp) up and running. The construction of glow plug engines was then stopped. After his apprenticeship in his father's company and his engineering exam at the Copenhagen Technical College in 1928, Peter Callesen did an internship at the Rostock Neptune shipyard. In 1936 he took over the management of the company in Apenrade.

By the outbreak of war, he had increased the production of Callesen diesel engines up to 100 hp. In addition to a petroleum engine from 1904, an older diesel engine of the 25 hp type 1 95 A R from 1946 is also kept in the company's recreation room. The Apenrade engine factory - now managed by Hans Heinrich Callesen (1941) in the third generation - still produces "tailor-made package solutions" for ship engines: slow-running diesel engines including reversing gear and propeller, and has been producing Bukh engines from 10 to 48 hp since 1994.

Eckernförde

Karl Rehbehn (1892 Eckernförde-1972 Eckernförde) was the son of a fisherman. He trained in the Eckernförde metalworking shop Lorenzen and then worked from 1911 to 1914 in the Kiel Germania shipyard, and from 1915 to 1918 in the Eckernförde naval torpedo testing facility. In 1919 he set up his own business as the "Eckernförder Motorenfabrik" in the Borby district, which had around 45 employees in the mid-1920s. Since 1922, glow plug engines have been built there: single-cylinder two-stroke engines of 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25 HP as well as two-cylinder engines of 20, 35, 60 and 80 HP - for boats with reversing gear or with reversing propellers.

They were eligible for Reich loans. It is no longer possible to determine where Karl Rehbehn got the gray and malleable cast iron and the crankshaft blanks. Central lubricators from Bosch were used as oilers. The vertical centrifugal regulator was mounted behind the cylinder, driven by a gear ring on the crankshaft. The centrifugal weights were encapsulated, as was the hanging wedge and the rotating cam disk underneath, which controlled the drive of the horizontally operating fuel pump piston. From 1922 to 1964, 350 glow-bulb engines were built in Eckernförde - the last of them with "quick heaters": crude oil-compressed air burners permanently mounted on the cylinder head, which reused compressed air stored in bottles from the cylinder.

Most of these ECKE machines were installed in fishing vessels and in cargo motor sailors. To a lesser extent, they were used for stationary operations in trade and agriculture. The maritime customer base hardly extended beyond the western part of the German Baltic coast. Nothing is known about the export of ECKE engines. As a secondary production, Rehbehn built food processing machines and high-performance net winches for fishing boats. The factory was also authorized as a repair shop for Krupp-Modag diesel. Karl Rehbehn only advertised his products to a modest extent. His Eckernförde engine factory was continued until 1981 by Otto Trede and until 1985 by Jörg Arendt. The buildings at the harbor were demolished in 1987. One ECKE engine each is now located in the Eckernförde Local History Museum and the Dithmarscher State Museum in Meldorf.

Kiel-Friedrichsort

In 1877, the German Navy built a torpedo depot in Friedrichsort (north of Kiel), which from 1891 was called the "Imperial Torpedo Workshop": a company specializing in the manufacture of torpedoes. The end of the First World War

also meant the end of this armaments production on the banks of the fjord. Here too, it was necessary to develop new branches of employment based on the existing high-quality special machine tools, which not only allowed workers to continue to work, but also made it possible to make them economically viable for private industry.... Naturally, it was obvious to turn to the manufacture of products that were needed in shipping, because this group of customers drove past the front door every day. 6

The company, which became Reich property in 1919 and has been operating as "Deutsche Werke Friedrichsort AG" since 1920, was already producing piston steam engines, diesel engines, hot-plug engines and outboard motors in 1921: the hot-plug engines as two-stroke engines with 8 to 90 hp, the diesel engines as two- and four-stroke engines, either with or without a compressor. The Friedrichsort outboard motors were built as two-cylinder two-stroke engines with power ratings of two to five hp. There is no information about which engine parts were supplied or manufactured in-house. Gray cast iron and colored cast iron must have been produced in-house, as the company advertised its "iron and metal castings". Nothing is known about the origin of the crankshaft blanks and the oilers. The Deutsche Werke regulator for the glow plug engines was of an unusual type: a completely enclosed axle regulator at the rear end of the crankshaft, with horizontally mounted, spring-braked flywheels. A sliding sleeve and inclined cams controlled the fuel pump, which was positioned at right angles and horizontally. The engine designers are unfortunately not named in the 1965 commemorative publication; no statement is made about the extent of production either.The manufacture of glow plugs and probably also of outboard motors was stopped in Friedrichsort in 1926. In 1930, the DW glow plug engines were no longer eligible for a Reich loan. The manufacture of marine diesel engines continued to flourish. Until the start of the war (1939), the Friedrichsort four-stroke engines with 33 to over 500 hp were advertised in trade journals. In addition to marine engines, the factory on the fjord also manufactured capstans, winches, piston pumps and alternator units and built fishing boats. Product advertising always featured the distinctive D logo of the resting lion.

Hot-plug engines from Friedrichson were very popular in the German fishing industry and with our coastal fishermen. In 1958, out of a total of 51 ship engines, three 18 hp and eight 36 hp Dütsche Werke engines were still in use on the Pomeranian lagoon and Bodden waters. There is no information about the customers of the outboard engines: were they sports sailors, were they recreational fishermen? A 18 hp Friedrichson hot-plug engine, which comes from an Eibever, is in the Lauenburg Inland Shipping Museum; a 24 hp two-cylinder hot-plug engine salvaged from the wreck of a Rügen passenger ship in the Mönchgut Museum in Göhren on Rügen was demolished in important components by amateur handling. The Kiel Ship Museum preserves a 240 hp Deutsche Werke 6-cylinder four-stroke diesel engine delivered in 1943. The factory, which was again largely integrated into armaments production during the Second World War, was renamed HOLMAG in 1945, then MaK in 1948 and still exists today.

Kiel

Carl Daevel (1848 Niewohld Kr. Plön -1908 Kiel), trained as an engineer, bought the Kiel machine factory of Sievers & Weyhe on Kirchhofallee in 1880 and built there - initially with 30 employees, by 1900 with over 120 - high-speed steam engines (to drive dynamos) as well as traction engines and pumps. In 1888 he was granted a patent for a ship's screw propeller with adjustable blades. In 1890, the annual report of the Kiel Chamber of Industry and Commerce for Daevel's factory on Kirchhofallee mentioned for the first time the construction of gas and petroleum engines. From 1898 the company was known as "Kieler Maschinenbau AG, formerly Daevek". In those years the German Sea Fishing Association tried to interest a medium-sized company in the construction of simple, robust and reliable boat engines in the style of the Danish hot-head engines. In the winter of 1904, thanks to the intervention of the engineer Duge in Kiel, Kiefer Maschinenbau AG, formerly Daevel, was able to get the company to look into the construction of a fishing engine. The factory's engineers were repeatedly shown the "Alpha" system engines and demonstrated them in operation, and were also informed of all the experiences made with the engines to date... The Daevel engine has been in operation since March 1905. 7

This was a two-cylinder four-stroke glow-head engine of 8 hp, which was later described in great detail by Romberg.8 Nothing is known about the manufacturing conditions, however: one can assume, however, that all the gray, malleable and colored cast iron parts, as well as the lubricating device, were manufactured in the Daevel factory itself; certainly also the Daevel regulator: the front journal of the crankshaft drove a horizontal control shaft, offset in height and laterally, via two gear wheels, on the rear end of which sat a rotating open housing for two spring-braked flywheel weights housed in it. The centrifugal movement of these weights was transferred by angle levers and joints through recesses in the housing wall to the front of the regulator, where the angle levers could move a sleeve-shaped sliding sleeve to the right or left. A stepped cam sat on the sleeve, which controlled the movements of the vertically operating fuel pump piston. This type was later adopted or modified by Jörgensen and the Deutsche Werke, but also in Laboe, Greifswald, Saßnitz and Freest.

Notes:

1 Rudolph, Wolfgang: Ship engines in the museum. In: Contributions to the folklore of Western Pomerania. Rostock 1989, pp. 57-60.

Boat engine construction in Pomerania - more than a curiosity? In: Journal for East German Folklore 37, 1994, pp. 263-283.

Faaborg, Svend Aage: Aabenraa Motorfabrik gennem ni artier. Aabenraa 1989.

Kaiser, Joachim: HMG and the development of the engine industry. In: Sailors at the turn of the century. Norderstedt 1977, pp. 1 83-1 94.

Meyer, Vicco: Ship diesel engines. In: Herben Karting: The motor sailors of the Krupp-Germania shipyard. Rendsburg 1987, pp. 235-245.

Biström, Lars & Bo Sund in: Svenska barmotorer. Skärhamn 1991 .

Thorsvik, Eivind: Mekanisering av fiskeflåten. In: Volund, Oslo 1972, pp. 9-132.

Dam-Hansen, B01·ge: Alpha Diesel - 1 00 ar i foreign rift. Frederikshavn 1983.

Rasmussen, Alan Hjorth: Fra oil motor til skibs hydraulics. AIS Motorfabriken “Dan” 1887-1987. Esbjerg 1987.

MortenS0n, Ole: Motorfabrikken >>Danmark« and the fynske marine motorer. In: Fynske Minder, Odense 1981, pp. 109-127.

2 Lübbert, Hans: The introduction of motors and shear nets into German sail fishing on North Sea fishing vessels. Berlin 1906 (Abh. German Sea Fishing Association, Vol. 8).

Siebolds & Block: The introduction of motors into sail fishing in the Baltic Sea. Berlin 1 907 (Abh. German Sea Fishing Association, Vol. 9).

Dittmer/Liekfeldt/Romberg: Motors and winches for fishing. Munich/Leipzig 1911.

3 The sea fishing motors eligible for Reich loans. In: Mitteilungen des Dt. Sea Fishing Associations 44, 1928, pp. 285-287.

4 The engine construction of large ship diesel engines at the Kiel Germania shipyard (from 1907) and the licensed construction of Sulzer diesel engines at the Kiel Howaldt shipyard (from 1911) are not taken into account here.

5 For the area under investigation, the boat engine construction by Kærton Peter Rasmussen Eg in Sonderburg/Sønderborg (from 1935) can also be included - after 1948 continued by Hans Sønnichsen & Heinrich Schnoor until 1952. Single and two-cylinder petrol engines of the brand EKKO were produced.

6 MaK - 100 years of the Friedrichsort plant. Kiel 1965, p. 17.

7 Lübbert (see note 2), p. 65-67. The civil engineer Duge mentioned on page 66 is the owner of the Kiel engineering firm Duge & Werner.

8 Romberg, F.: The oil engine in German sea fishing operations. In: Jb. d. Schiffsbautechnischen Gesellschaft 13, 1912, pp. 173-253.

9 In: Annual reports of the Kiel Chamber of Industry and Commerce for 1904 to 1911.

10 Matthiessen, Hugo: Fishing engines. Berlin 1 920, pp. 22-24.

11 What is hidden behind the abbreviation HAEM (= HM) has not yet been determined.

12 Müller, Bruno: Type tables of boat and outboard engines. Berlin 1922, pp. 6 1-62; Reibestahl, Paul: Repairs to boat engines. Berlin 1 928, pp. 184-185; Brix, Adolf: Practical shipbuilding and boat building. Berlin 7 1929, p. 265.

13 Festschrift zum 50 Jubiläumsjahr der HAGENUK. Kiel 1949, p. 5.

14 Müller, Bruno: Typtabellen von Boot- und Außenbordmotoren. Berlin 1 922, pp. 53-55; Reibestahl und Brix (see note 1 2).

15 In order to prevent white glow caused by premature ignition and possible bursting of the (non-water-cooled) glow head, older machines of this type could be sprayed with (fresh) water into the combustion chamber using a second, weaker and manually adjustable injection pump, where it immediately evaporated and had a cooling effect.